The Golden Book of Cleveland was as big as a queen sized bed, contained more than half a million signatures, and weighed more than two tons. If it still exists, it is the largest book in the world. But its whereabouts have been unknown since 1937.

Cleveland, Ohio played host to the Great Lakes Exposition of 1936-37, its own effort at a World’s Fair that attracted more than 7 million visitors over its two-year run. The expo was “conceived as a way to energize a city hit hard by the Great Depression” and featured rides, sideshows, botanical gardens, cafes, art galleries, and other attractions. Notable among these was the Golden Book of Cleveland, billed as the largest book in the world. From Cleveland Magazine:

The Golden Book of Cleveland, official registration book of the Great Lakes Exposition, stood inside the main entrance on St. Clair Avenue during the expo’s first season. It was 7 feet by 5 feet and 3 feet thick, with 6,000 pages — about the size of a queen-size bed. It weighed 2 1/2 tons. The Golden Book had spaces for 4 million signatures. By Aug. 17, 1936, halfway through the expo’s season, 587,400 people had signed it.

According to Cleveland Magazine, the expo’s organizers intended to donate the book to a local historical society. (“The idea was that fairgoers or their descendants could visit Cleveland again years later, look on the page number recorded in their booklet and find their signature.”) The book disappeared from expo coverage in Cleveland newspapers after August 1936, however, and after the expo ended it vanished from the public record entirely. Cleveland Magazine checked three libraries’ archives, a dozen books of newspaper clippings from the expo, more than a dozen Cleveland historians, the Western Reserve Historical Society, and the Ohio Historical Society, and none could account for the book’s ultimate fate.

So where might Cleveland’s lost bed-sized book have ended up? Some speculate that it was simply destroyed following the expo. However, after Cleveland Magazine published an article about the book in 2006, a man named Al Budnick claimed that his father had sold the book to a Tucson doctor in the early 1950s. While no physical trace of the book (nor the identity of its alleged purchaser) has since turned up, you can read more in a 2007 article in the Arizona Daily Star.

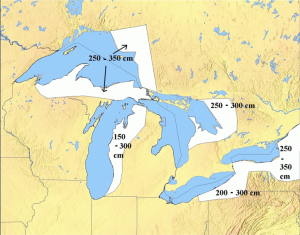

snow

snow